Interview as part of the American Next, a special project exploring the hopes, fears and changing expectations of Missouri’s next generation in challenging times / 3734 words / The Columbia Missourian

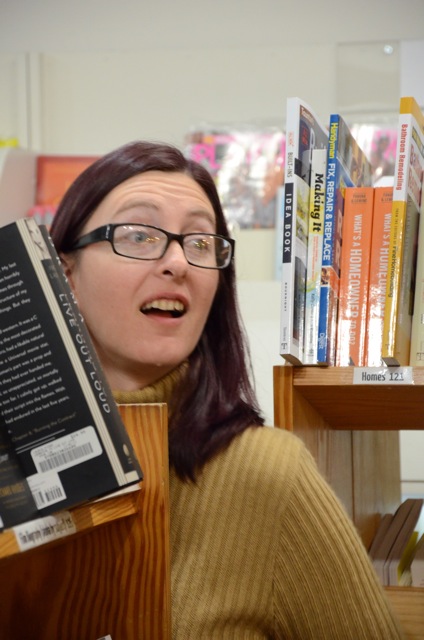

ST. LOUIS — Sarah Johnson, 38, is happily employed at Left Bank Books, an independent bookstore with two locations in St. Louis. She goes by “Jonesey” and lives alone with her two cats, Ethel and Boris. I interviewed Jonesey at Pi, a restaurant in the Central West End, across the corner from Left Bank Books, where she was headed to work later that morning. She blogs at www.joneseythewordslinger.blogspot.com. She tells her story.

It’s a really odd little story. I realized when I was 34 that what I wanted to do with the rest of my life was to be a librarian. And I wanted to learn how to fix books. And I really wanted to do that in places like after Hurricane Katrina, and after the flood in Iowa. Libraries fall through a lot of monetary aid cracks, yet they are an incredibly important part of any community.

They’re part of the legitimacy of communities because they provide a sense of history when you get to books and records and the things that prove your right to exist in a place. Things like deeds, legal records, the original maps people drew to define the space you live in. And because our culture is so legalistic, we need the paper trail.

Humans express themselves visually, and one way of visually expressing yourself is in the written language. It also provides cultural legitimacy in the sense that other people like me have written books about the things I am experiencing. So that puts me on a spectrum. And if I’m on a spectrum, then I exist. If I can place myself somewhere measurable, then I have a history. If I have a history, then I have a present. If I have a present, then I have a future.

I have one younger sister, five-and-a-half years younger. She is married to her second husband. They live in Utah. She has a 13-year-old daughter by her first marriage and a 7-year-old boy by her second. My niece lives here in Eureka with her father and stepmother.

I figured I’d come to St. Louis. I wanted to be here while my niece went through high school. I have no children. I’ve been married and divorced twice. I live with cats. I knit. I read books. I’m really happy.

Growing up

I grew up in the most southwestern neighborhood in Chicago. It’s called Beverly/Morgan Park. The neighborhood was a very welcoming Irish Catholic Democratic neighborhood.

I lived, literally, on the wrong side of the tracks, even though both of my parents went to work in offices, had titles, wore ties. There was a lot of the standard husband who worked in a union job, had done his apprenticeship. Probably lived within three or four blocks of where his parents lived. Wife stayed home with the kids. Now, staying home with the kids means running around after them and taking them to school. But that was most everybody in the neighborhood, except for us.

My dad’s from Lincoln, Nebraska. My mom’s from Blencoe, in western Iowa. It was a safe neighborhood that had a lot of families and a lot of churches. And, that was the deal. That was where we bought.

Libraries

I lived in Lincoln, Nebraska, for 12 years. I was working at the public library there at the time, and one of my co-workers and I, who were really good friends, started thinking about how to run a library well. You have to answer the question, what is a library? Which is a really, really big and difficult question it turns out nobody actually knows the answer to — even though everybody acts like they do. There are so many answers.

A library is a place where the books are. A library is a place where you go to use the Internet. A library is the place where you look up things. Where you ask people questions. Where you meet with people from your community. Where you study. The best definition that I’ve ever heard is that a library is the place where you have access to information and therefore can gain knowledge. Because a library isn’t really about books anymore.

Now I work in a bookstore. I don’t believe that bookstores, especially independent bookstores, are just about books. I believe that they are about access to (good) books.

Especially a place like Left Bank or an independent bookstore, this isn’t about convenience. We don’t have Westerns and romance novels and a lot of the (popular) series. We have a lot of really good books that are written by people you might not have heard of. Books that would be harder to find in Walmart, in a grocery store, or the newsstand, or your local school library.

Left Bank Books in St. Louis (photo by Rick Agran and Hilary Niles)

I love what happens when you open a book, and your world just shifts.

I’m reading a travelogue right now called “All the Roads Are Open,” by Annemarie Schwarzenbach. In 1939, she and a companion drove across Afghanistan from Switzerland. They drove this old Ford, and they drove through Iran, which was still Persia, parts of it anyway, and through Afghanistan, into India. She describes the Hindu Kush, and I have to work to remember that I’m not in the mountains when I’m reading it.

The thing I really enjoy about good writing — that moment when you are sucked into a book — is that I am allowed to experience someone else’s confident and clear perspective that I might never have had otherwise. I am challenged to leave my own perspectives behind. I think that the more we narrow our world, the more barren it becomes.

And I think that that’s something that’s very easy to do when bestsellers are all that are thrown at you, when the newest and the shiniest are all that are available.

That’s like so many of the messages that we get about fitting into a very well-defined mold. And that path leads you to … some nirvana of success? I don’t know. I’ve never been able to figure that one out.

I haven’t lived with a television for a really long time. In Lincoln I had a roommate who was like a cable addict. So that was eight months in 2007. And then before that, it had been, three years? I had a television that was hooked up to a DVD player, so we watched DVDs.

But I don’t take the news. I don’t take newspapers. I don’t buy them, I don’t subscribe to them. I don’t pick them up. I will occasionally read The Wall Street Journal. And that’s always an interesting experience because I get really angry. I feel like the news-reading public are being told things that are not justified. I always wonder, what aren’t we being told? I’m not a conspiracy theorist, but I do think there are times when you look at the paper or you listen to the news and why is that senator so important today? What really happened that that guy or that woman is so important, instead of something else going on?

Particularly because it is an election year, and I really despise what happens when people start slinging mud at each other. I think they become very small, and these are the people who want the biggest job in the country. They are so diminished in their behavior that I don’t even want to be part of the process. Even though really, I do want to be part of the process! Because I do believe in active involvement in a democracy. I think that’s the only way that it functions. So election years always challenge me.

Family

My dad was a geographer for the Corps of Engineers. My mom worked in the training and implementation department of an insurance company, and they trained people how to use computers. My dad quit the Corps and got his MBA, became a travel agent. Then my mom’s department was disbanded. But she had always loved teaching people how to use their computers, so she started her own business.

One night she was overbooked, so my dad took a class of hers. And he just got bit. He loved the teaching, decided that was what he wanted to do. So in 1992, he moved to Wichita, Kan., with my sister. My mom stayed in Chicago with the business and my dad got his master’s degree in anthropology at Wichita State University, and taught his way through.

I moved to Lincoln in ’98. I was 25. In ’99 my dad, my sister and my niece moved to Lincoln. My dad started his doctoral program. He started in anthropology, but he ultimately got his degree in geography from University of Nebraska-Lincoln. And is now teaching!

My mom’s business kept going. We finally sold the house in Chicago so she got this little apartment in La Grange Park, Ill. We got this delighted phone call from her, right after we moved her. The message was, “It’s 70 degrees below zero with the wind chill and I’m not paying heat on an eight-room house!”

Then in 2003 she was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. So she moved to Nebraska and lived with my dad again. They’ve been married for 43 years. And they’re really good friends. They get each other. And so yeah, they lived apart. My mom’s convinced that’s one of the reasons that it worked, was that they were both only children, so the idea of being alone was not awful. And it didn’t challenge the fundamentals of their marriage in any way.

I knew I wasn’t going to be able to do what I wanted to do in Lincoln. My career, socially — I had just hit stall there.

So I asked my folks if I could live with them for a year once my dad got his degree and they went to wherever he was going to go and teach. They said sure, which was just an amazing gift. We ended up moving to this small town in northwestern Missouri — 11,000 people. Maryville, Mo.

That’s a really small town. A lot of parks. No sidewalks. There were like six (independently owned) restaurants, and we went to all of them within the space of a month. Everything else was fast food. It was horrifying. The farmers market was a joke.

It’s a culture of poverty. During the Depression, people worked really hard. They didn’t know they were poor. Everybody had a garden, nobody had shoes. Everybody rode horses to school. I volunteered for the historical society for a little while, watching videos of interviews they had done with people who had lived during the Depression and World War II. They were just living, surviving, making it happen, with their families, going to church, going to school. They had a very uncomplicated moral code. And people lived by it.

I’m sure that there was separation based on class and what not, but these people were not lazy! I don’t know what happened. I don’t know if it was the car. I don’t know if you can point to any one sort of governmental thing. I don’t know if you can point to any one economic thing. But I do know that the city now, just Kawasaki and Energizer are the two big employers outside of the university.

The separation between town and gown is palpable. There is a huge population of south Indian students, from Hyderabad. And the town has done nothing to welcome them. The only grocery stores where you can get Indian food is in Kansas City.

Religion

I grew up in this Congregationalist church. It was interdenominational. It was a covenant church, and so that meant that we had a covenant with each other, and with God.

The neighborhood that I grew up in was predominantly Catholic, St. Barnabas Parish. There was a Unitarian church up the hill, there was a Good Sam church that met in the Methodist Church. There were Episcopalian churches. There was every Protestant denomination that you could think of. So my experience of religion started as my experience of church. I left the church sort of slowly because it just seemed really hypocritical. I saw my parents doing what they said they believed in, and I saw other people’s parents not.

My parents said that they believed in charity, and they volunteered to teach people English. We bought Christmas presents and brought them to poor people. They walked the walk. Like anybody, they’re imperfect. But still there was this idea of consistency. And they were really good hosts and they were always willing to talk to people, which was something that I saw other members of my church not doing.

Then when I was 16, I had accidentally dyed my hair purple. It was supposed to be burgundy. And it was Lent.

Left Bank Books in St. Louis (photo by Rick Agran and Hilary Niles)

So we’re at Lenten dinner. I’m around people I’ve known since I was 6 years old. And I go sit at a table with some of them, and they did not acknowledge me. They wouldn’t look at me, they wouldn’t make space for me. It was like I didn’t exist.

I spent a few years being really angry with Christians. And then I got over it. Sort of slowly. It was sort of a series of things that happened, beginning with a very real sense of hypocrisy in my own behavior. There was this sort of parental voice in the back of my head that you don’t really want to listen to but that you know is saying the right thing. I mean just being angry at somebody for having faith. What’s the point?

There was also this lack of understanding. I was not trying to reach out and find out what people actually believed. I was labeling them — based on a label that they had chosen. Which is incredibly discompassionate.

And then the mother of a friend passed away. She was diabetic. She went into a coma and never came out. And I really, really liked her. She was always really sweet to his friends because he was an odd kid, like me, and so didn’t really have a ton of friends. And another person had passed away from my church. He had been really good to all of us kids, and he had died the day after my friend’s mom died. So I flew back to Chicago and ended up going to two funerals in one day.

The first service was for the man at my church. He had lived a good long life and he was involved in everything. And we had all known him. He was nice. He was thoughtful. He knew all the kids. But the service was this sterile recitation of his accomplishments.

Our religion was defined almost as “not Catholic.” That was as close as you ever got to understanding what your relationship to Christ was supposed to be. It was like, “You are not Catholic. So, whatever a Catholic believes, you don’t!” Which is really interesting to me because we lived in a Catholic neighborhood. We all had Catholic friends. But we didn’t really understand them.

We actually had a fairly well integrated neighborhood. The big groups were black and white. But because of how I experienced the neighborhood, to me the big groups were Protestant, Catholic and Baptist. In my mind, you were defined by what church you went to on a Sunday morning, and what youth group you went to on a Wednesday afternoon. And whether or not you sang in choir. That was how I parsed everybody.

Now, if I define people, it’s by the books they read. But that’s only in the store, and that’s only when I get to know people.

I define people based on whether they shop for convenience or for value. I take public transport, I walk. I don’t have a car. I don’t have a credit card. My experience of life is incredibly different than 95 percent of the people that I meet, just because I don’t experience advertisements, television shows or red lights.

Divorce

I ended up on the bottom end of women-who-get-divorced statistics. I owned a house out in Nebraska that I eventually lost. The house foreclosed in 2005. I was able to afford the house with my husband when I bought it. The mortgage we got, the interest rate, everything, that wasn’t the problem. It was the other stuff that was involved and we couldn’t sustain. We didn’t know enough. We shouldn’t have bought the house. Shouldn’t have been married!

But, whatever. I was the one who had the job. He had just started his own business. So the bank gave me the mortgage. When “we” split up and “we” lost the house, I lost the house. And I didn’t have a car. So when I kicked him out, I lost the car.

Left Bank

I love this job. I have no intention of leaving. And I’m about to get benefits. Health, dental and vision.

My credit score is something that I’ve been thinking about in a very real way because this year, the foreclosure drops off. But I still have student loan debt that I have to deal with and some other little things.

I had a job for three years as a secretary at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. So I had retirement built up, but when I quit that job, it was right around the time I was getting my divorce, and I was just so burnt out and I needed a break, and so I cleaned out my retirement and just took care of myself for six months. But that was it: that was the only time I have ever even had a meaningful retirement account.

It’s small steps. And I’m sort of starting from square one except for that I’m actually really happy in what I do, and the people that I work with, and the city that I’m in.

I didn’t expect to love this city. I didn’t expect to find this job. I expected to work as a temp in offices for a couple of years, build up some savings, pay off some of my debts, get a fancy-schmancy apartment, you know. Be stylish. And start taking book-binding classes. Then learn how to restore books. That’s a slow process; books are not fast. And then this came along.

It shifted everything and slowed it down a little bit more. But it gave me a place to actually start from. Build relationships and then build a life that is compassionate in a way that I want it to be compassionate.

I recognize that I don’t share the same future ideals that a lot of people do. I don’t necessarily see security in a home, because I have lost a home. I don’t see security in a car, because it’s so transient. I don’t see security in money. And I don’t necessarily even want a whole lot of security because I feel like you give up a lot.

A lot of people give up the freedom to make their own decisions. About with whom they’re going to be friends, what they’re going to do with their money. About where they go and what they do.

When you own a home, it’s the thing that you do to establish yourself and to be safe. You have to ensure that the house is safe, one way or the other. Which means that you might or might not be effectively using your skills. Or happy at all. Or healthy at all, because you’re working for security, in a job that you know is not going to go away in order for you to have a home that provides you with security and a car that means that you don’t have to take the bus, so you are secure, you are safe from being late for everything. Because you have your own means of transportation!

And in a larger context, you have to support policies that allow you to maintain your sense of security. You don’t want somebody taking your job, you don’t want somebody taking your children’s job. You don’t want somebody taking your tax dollars.

People are dying all over the world because of wars that are fought in order to secure access to resources like copper, magnesium, rare earths, oils, things that are used in all of our stuff, in order to allow us to maintain our lifestyles. As if that’s the best, like we have the right.

And that was where I came to ultimately with this idea of the American Dream. My real problem with it is not that people want to have a better life for their children than they had for themselves. Not that they want to pass on their ideas of democracy and of freedom. It’s that, in this country, the messages we get require that everything be about winning. And there is no such thing as winning without somebody else losing.

Left Bank Books in St. Louis, Mo. (photo by Rick Agran and Hilary Niles)

Living the dream

Creative resourcefulness and community. That’s my dream. To be a part of a community, to be allowed to be creative in that community, a positive member of it, and to be resource responsible. It comes from what my grandmother told me, how my parents were raised, how I was raised. We had a garden in Chicago. They canned. My parents both sewed. We read books, talked to each other. We watched television one night a week.

At no point did I feel like we were not being American. I never felt like we were doing something subversive. It was only when I got into the outside world that I realized that, apparently, that was wrong!

Take responsibility for your own action. That is something that I would really like to see. If you want things to change, you change them. For yourself. Because nobody else is going to do it for you.

We have the right to make so many of our own decisions, and yet we don’t do it, at all. What we buy. What news we listen to. What books we read. How we read them. The music we listen to.

So that’s where I ultimately get to: I have the right to define my life in a way that doesn’t make me somebody I don’t respect. In theory, that’s the American Dream, right? I get to define my own life.